The official Terraform Getting Started documentation does a good job of introducing the individual elements of Terraform (i.e. resources, input variables, output variables, etc), so in this guide, we’re going to focus on how to put those elements together to create a fairly real-world example. In particular, we will provision several servers on AWS in a cluster and deploy a load balancer to distribute load across that cluster. The infrastructure you’ll create in this example is a basic starting point for running scalable, highly-available web services and microservices.

This guide is targeted at AWS and Terraform newbies, so don’t worry if you haven’t used either one before. We’ll walk you through the entire process, step-by-step:

You can find working sample code for the examples in this blog post in the Terraform: Up & Running code samples repo. This blog post corresponds to Chapter 2 of Terraform Up & Running, “An Intro to Terraform Syntax,” so look for the code samples in the 02-intro-to-terraform-syntax folders.

Set up your AWS account

Terraform can provision infrastructure across public cloud providers such as AWS, Azure, Google Cloud, and DigitalOcean, as well as private cloud and virtualization platforms such as OpenStack and VMware. For just about all of the code examples in this blog post series, you are going to use AWS. AWS is a good choice for learning Terraform because of the following:

AWS is the most popular cloud infrastructure provider, by far. It has a 32% share in the cloud infrastructure market, which is more than the next three biggest competitors (Microsoft, Google, and IBM) combined.

AWS provides a huge range of reliable and scalable cloud-hosting services, including Amazon Elastic Compute Cloud (Amazon EC2), which you can use to deploy virtual servers; Auto Scaling Groups (ASGs), which make it easier to manage a cluster of virtual servers; and Elastic Load Balancers (ELBs), which you can use to distribute traffic across the cluster of virtual servers. Side note: if you find the AWS terminology confusing, be sure to check out Amazon Web Services in Plain English.

AWS offers a Free Tier for the first year that should allow you to run all of these examples for free or a very low cost. If you already used your Free Tier credits, the examples in this blog post series should still cost you no more than a few dollars.

If you don’t already have an AWS account, head over to aws.amazon.com and sign up. When you first register for AWS, you initially sign in as the root user. This user account has access permissions to do absolutely anything in the account, so from a security perspective, it’s not a good idea to use the root user on a day-to-day basis. In fact, the only thing you should use the root user for is to create other user accounts with more-limited permissions, and then switch to one of those accounts immediately (see IAM best practices).

To create a more-limited user account, you will need to use the Identity and Access Management (IAM) service. IAM is where you manage user accounts as well as the permissions for each user. To create a new IAM user, go to the IAM Console, click Users, and then click the Add Users button. Enter a name for the user, and make sure “Access key — Programmatic access” is selected, as shown below (note that AWS occasionally makes changes to its web console, so what you see may look slightly different than the screenshots in this blog post).

Click the Next button. AWS will ask you to add permissions to the user. By default, new IAM users have no permissions whatsoever and cannot do anything in an AWS account. To give your IAM user the ability to do something, you need to associate one or more IAM Policies with that user’s account. An IAM Policy is a JSON document that defines what a user is or isn’t allowed to do. You can create your own IAM Policies or use some of the predefined IAM Policies built into your AWS account, which are known as Managed Policies.

To run the examples in this blog post series, the easiest way to get started is to add the AdministratorAccess Managed Policy to your IAM user (search for it, and click the checkbox next to it), as shown below.

Note: I’m assuming that you’re running the examples in this blog post series in an AWS account dedicated solely to learning and testing so that the broad permissions of the AdministratorAccess Managed Policy are not a big risk. If you are running these examples in a more sensitive environment — which, for the record, I don’t recommend! — and you’re comfortable with creating custom IAM Policies, you can find a more pared-down set of permissions in the code examples repo.

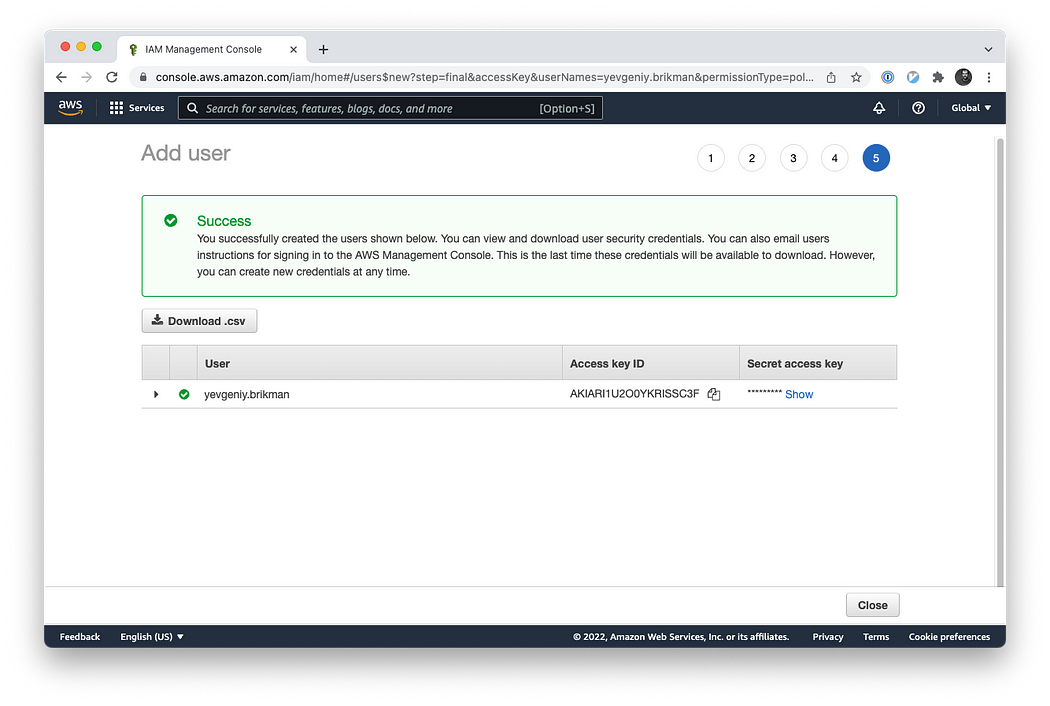

Click Next a couple more times and then the “Create user” button. AWS will show you the security credentials for that user, which consist of an Access Key ID and a Secret Access Key, as shown below.

You must save these immediately because they will never be shown again, and you’ll need them later on in this tutorial. Remember that these credentials give access to your AWS account, so store them somewhere secure (e.g., a password manager such as 1Password, LastPass, or macOS Keychain), and never share them with anyone.

After you’ve saved your credentials, click the Close button. You’re now ready to move on to using Terraform.

Install Terraform

The easiest way to install Terraform is to use your operating system’s package manager. For example, on macOS, if you are a Homebrew user, you can run the following:

$ brew tap hashicorp/tap

$ brew install hashicorp/tap/terraform

On Windows, if you’re a Chocolatey user, you can run the following:

$ choco install terraform

Check the Terraform documentation for installation instructions on other operating systems, including the various flavors of Linux.

Alternatively, you can install Terraform manually by going to the Terraform home page, clicking the download link, selecting the appropriate package for your operating system, downloading the ZIP archive, and unzipping it into the directory where you want Terraform to be installed. The archive will extract a single binary called terraform, which you’ll want to add to your PATH environment variable.

To check whether things are working, run the terraform command, and you should see the usage instructions:

$ terraform

Usage: terraform [global options] <subcommand> [args]The available commands for execution are listed below.

The primary workflow commands are given first, followed by

less common or more advanced commands.Main commands:

init Prepare your working directory for other commands

validate Check whether the configuration is valid

plan Show changes required by the current configuration

apply Create or update infrastructure

destroy Destroy previously-created infrastructure

For Terraform to be able to make changes in your AWS account, you will need to set the AWS credentials for the IAM user you created earlier as the environment variables AWS_ACCESS_KEY_ID and AWS_SECRET_ACCESS_KEY. For example, here is how you can do it in a Unix/Linux/macOS terminal:

$ export AWS_ACCESS_KEY_ID=(your access key id)

$ export AWS_SECRET_ACCESS_KEY=(your secret access key)

And here is how you can do it in a Windows command terminal:

$ set AWS_ACCESS_KEY_ID=(your access key id)

$ set AWS_SECRET_ACCESS_KEY=(your secret access key)

Note that these environment variables apply only to the current shell, so if you reboot your computer or open a new terminal window, you’ll need to export these variables again.

In addition to environment variables, Terraform supports the same authentication mechanisms as all AWS CLI and SDK tools. Therefore, it’ll also be able to use credentials in $HOME/.aws/credentials, which are automatically generated if you run aws configure, or IAM roles, which you can add to almost any resource in AWS. For more info, see A Comprehensive Guide to Authenticating to AWS on the Command Line.

A Note on Default Virtual Private Clouds: All of the AWS examples in this blog post series use the Default VPC in your AWS account. A VPC, or virtual private cloud, is an isolated area of your AWS account that has its own virtual network and IP address space. Just about every AWS resource deploys into a VPC. If you don’t explicitly specify a VPC, the resource will be deployed into the Default VPC, which is part of every AWS account created after 2013. If for some reason you deleted the Default VPC in your account, either use a different region (each region has its own Default VPC) or create a new Default VPC using the AWS Web Console. Otherwise, you’ll need to update almost every example to include a vpc_id or subnet_id parameter pointing to a custom VPC.

Deploy a single server

Terraform code is written in the HashiCorp Configuration Language (HCL) in files with the extension .tf. It is a declarative language, so your goal is to describe the infrastructure you want, and Terraform will figure out how to create it. Terraform can create infrastructure across a wide variety of platforms, or what it calls providers, including AWS, Azure, Google Cloud, DigitalOcean, and many others.

You can write Terraform code in just about any text editor. If you search around, you can find Terraform syntax highlighting support for most editors (note that you may have to search for the word HCL instead of Terraform), including vim, emacs, Sublime Text, Atom, Visual Studio Code, and IntelliJ (the latter even has support for refactoring, find usages, and go to declaration).

The first step to using Terraform is typically to configure the provider(s) you want to use. Create an empty folder and put a file in it called main.tf that contains the following contents:

provider "aws" {

region = "us-east-2"

}

This tells Terraform that you are going to be using AWS as your provider and that you want to deploy your infrastructure into the us-east-2 region. AWS has datacenters all over the world, grouped into regions. An AWS region is a separate geographic area, such as us-east-2 (Ohio), eu-west-1 (Ireland), and ap-southeast-2 (Sydney). Within each region, there are multiple isolated datacenters known as Availability Zones (AZs), such as us-east-2a, us-east-2b, and so on (learn more about regions and AZs here). There are many other settings you can configure on this provider, but for now, let’s keep it simple.

For each type of provider, there are many different kinds of resources that you can create, such as servers, databases, and load balancers. The general syntax for creating a resource in Terraform is as follows:

resource "<PROVIDER>_<TYPE>" "<NAME>" {

[CONFIG …]

}

where PROVIDER is the name of a provider (e.g., aws), TYPE is the type of resource to create in that provider (e.g., instance), NAME is an identifier you can use throughout the Terraform code to refer to this resource (e.g., my_instance), and CONFIG consists of one or more arguments that are specific to that resource.

For example, to deploy a single (virtual) server in AWS, known as an EC2 Instance, use the aws_instance resource in main.tf as follows:

resource "aws_instance" "example" {

ami = "ami-0fb653ca2d3203ac1"

instance_type = "t2.micro"

}

The aws_instance resource supports many different arguments, but for now, you only need to set the two required ones:

ami. The Amazon Machine Image (AMI) to run on the EC2 Instance. You can find free and paid AMIs in the AWS Marketplace or create your own using tools such as Packer. The preceding code sets theamiparameter to the ID of an Ubuntu 20.04 AMI inus-east-2. This AMI is free to use. Please note that AMI IDs are different in every AWS region, so if you change the region parameter to something other thanus-east-2, you’ll need to manually look up the corresponding Ubuntu AMI ID for that region, and copy it into theamiparameter.instance_type. The type of EC2 Instance to run. Each type of EC2 Instance provides a different amount of CPU, memory, disk space, and networking capacity. The EC2 Instance Types page lists all the available options. The preceding example usest2.micro, which has one virtual CPU, 1 GB of memory, and is part of the AWS Free Tier.

Note: use the Docs! Terraform supports dozens of providers, each of which supports dozens of resources, and each resource has dozens of arguments. There is no way to remember them all. When you’re writing Terraform code, you should be regularly referring to the Terraform documentation to look up what resources are available and how to use each one. For example, here’s the documentation for the aws_instance resource. I’ve been using Terraform for years, and I still refer to these docs multiple times per day!

In a terminal, go into the folder where you created main.tf and run the terraform init command:

$ terraform initInitializing the backend...Initializing provider plugins...

- Reusing previous version of hashicorp/aws from the lock file

- Using hashicorp/aws v4.19.0 from the shared cache directoryTerraform has been successfully initialized!

The terraform binary contains the basic functionality for Terraform, but it does not come with the code for any of the providers (e.g., the AWS Provider, Azure provider, GCP provider, etc.), so when you’re first starting to use Terraform, you need to run terraform init to tell Terraform to scan the code, figure out which providers you’re using, and download the code for them. By default, the provider code will be downloaded into a .terraform folder, which is Terraform’s scratch directory (you may want to add it to .gitignore). Terraform will also record information about the provider code it downloaded into a .terraform.lock.hcl file. You’ll see a few other uses for the init command and .terraform folder later in this blog post series. For now, just be aware that you need to run init anytime you start with new Terraform code and that it’s safe to run init multiple times (the command is idempotent).

Now that you have the provider code downloaded, run the terraform plan command:

$ terraform plan

(...)

Terraform will perform the following actions:

# aws_instance.example will be created

+ resource "aws_instance" "example" {

+ ami = "ami-0fb653ca2d3203ac1"

+ arn = (known after apply)

+ associate_public_ip_address = (known after apply)

+ availability_zone = (known after apply)

+ cpu_core_count = (known after apply)

+ cpu_threads_per_core = (known after apply)

+ get_password_data = false

+ host_id = (known after apply)

+ id = (known after apply)

+ instance_state = (known after apply)

+ instance_type = "t2.micro"

+ ipv6_address_count = (known after apply)

+ ipv6_addresses = (known after apply)

+ key_name = (known after apply)

(...)

}

Plan: 1 to add, 0 to change, 0 to destroy.

The plan command lets you see what Terraform will do before actually making any changes. This is a great way to sanity-check your code before unleashing it onto the world. The output of the plan command is similar to the output of the diff command that is part of Unix, Linux, and git: anything with a plus sign (+) will be created, anything with a minus sign (–) will be deleted, and anything with a tilde sign (~) will be modified in place. In the preceding output, you can see that Terraform is planning on creating a single EC2 Instance and nothing else, which is exactly what you want.

To actually create the Instance, run the terraform apply command:

$ terraform apply

(...)

Terraform will perform the following actions:

# aws_instance.example will be created

+ resource "aws_instance" "example" {

+ ami = "ami-0fb653ca2d3203ac1"

+ arn = (known after apply)

+ associate_public_ip_address = (known after apply)

+ availability_zone = (known after apply)

+ cpu_core_count = (known after apply)

+ cpu_threads_per_core = (known after apply)

+ get_password_data = false

+ host_id = (known after apply)

+ id = (known after apply)

+ instance_state = (known after apply)

+ instance_type = "t2.micro"

+ ipv6_address_count = (known after apply)

+ ipv6_addresses = (known after apply)

+ key_name = (known after apply)

(...)

}

Plan: 1 to add, 0 to change, 0 to destroy.

Do you want to perform these actions?

Terraform will perform the actions described above.

Only 'yes' will be accepted to approve.

Enter a value:

You’ll notice that the apply command shows you the same plan output and asks you to confirm whether you actually want to proceed with this plan. So, while plan is available as a separate command, it’s mainly useful for quick sanity checks and during code reviews, and most of the time you’ll run apply directly and review the plan output it shows you.

Type yes and hit Enter to deploy the EC2 Instance:

Do you want to perform these actions?

Terraform will perform the actions described above.

Only 'yes' will be accepted to approve.

Enter a value: yes

aws_instance.example: Creating...

aws_instance.example: Still creating... [10s elapsed]

aws_instance.example: Still creating... [20s elapsed]

aws_instance.example: Still creating... [30s elapsed]

aws_instance.example: Creation complete after 38s [id=i-07e2a3e006]

Apply complete! Resources: 1 added, 0 changed, 0 destroyed.

Congrats, you’ve just deployed an EC2 Instance in your AWS account using Terraform! To verify this, head over to the EC2 console, and you should see something similar to this:

Sure enough, the Instance is there, though admittedly, this isn’t the most exciting example. Let’s make it a bit more interesting. First, notice that the EC2 Instance doesn’t have a name. To add one, you can add tags to the aws_instance resource:

resource "aws_instance" "example" {

ami = "ami-0fb653ca2d3203ac1"

instance_type = "t2.micro" tags = {

Name = "terraform-example"

}

}

Run terraform apply again to see what this would do:

$ terraform apply

aws_instance.example: Refreshing state...

(...)

Terraform will perform the following actions:

# aws_instance.example will be updated in-place

~ resource "aws_instance" "example" {

ami = "ami-0fb653ca2d3203ac1"

availability_zone = "us-east-2b"

instance_state = "running"

(...)

+ tags = {

+ "Name" = "terraform-example"

}

(...)

}

Plan: 0 to add, 1 to change, 0 to destroy.

Do you want to perform these actions?

Terraform will perform the actions described above.

Only 'yes' will be accepted to approve.

Enter a value:

Terraform keeps track of all the resources it already created for this set of configuration files, so it knows your EC2 Instance already exists (notice Terraform says Refreshing state… when you run the apply command), and it can show you a diff between what’s currently deployed and what’s in your Terraform code. The preceding diff shows that Terraform wants to create a single tag called Name, which is exactly what you need, so type yes and hit Enter.

When you refresh your EC2 console, you’ll see something similar to this:

Now that you have some working Terraform code, you may want to store it in version control. This allows you to share your code with other team members, track the history of all infrastructure changes, and use the commit log for debugging. For example, here is how you can create a local Git repository and use it to store your Terraform configuration file and the lock file:

git init

git add main.tf .terraform.lock.hcl

git commit -m "Initial commit"

You should also create a .gitignore file with the following contents:

.terraform

*.tfstate

*.tfstate.backup

The preceding .gitignore file instructs Git to ignore the .terraform folder, which Terraform uses as a temporary scratch directory, as well as \.tfstate files, which Terraform uses to store state (in How to Manage Terraform State, you’ll see why state files shouldn’t be checked in). You should commit the .gitignore* file, too:

git add .gitignore

git commit -m "Add a .gitignore file"

To share this code with your teammates, you’ll want to create a shared Git repository that you can all access. One way to do this is to use GitHub. Head over to GitHub, create an account if you don’t have one already, and create a new repository. Configure your local Git repository to use the new GitHub repository as a remote endpoint named origin, as follows:

git remote add origin git@github.com:<YOUR_USERNAME>/<YOUR_REPO>.git

Now, whenever you want to share your commits with your teammates, you can push them to origin:

git push origin main

And whenever you want to see changes your teammates have made, you can pull them from origin:

git pull origin main

As you go through the rest of this blog post series, and as you use Terraform in general, make sure to regularly git commit and git push your changes. This way, you’ll not only be able to collaborate with team members on this code, but all of your infrastructure changes will also be captured in the commit log, which is very handy for debugging.

Deploy a single web server

The next step is to run a web server on this Instance. The goal is to deploy the simplest web architecture possible: a single web server that can respond to HTTP requests:

In a real-world use case, you’d probably build the web server using a web framework like Ruby on Rails or Django, but to keep this example simple, let’s run a dirt-simple web server that always returns the text “Hello, World”:

#!/bin/bash

echo "Hello, World" > index.html

nohup busybox httpd -f -p 8080 &

This is a Bash script that writes the text “Hello, World” into index.html and runs a tool called busybox (which is installed by default on Ubuntu) to fire up a web server on port 8080 to serve that file. I wrapped the busybox command with nohup and an ampersand (&) so that the web server runs permanently in the background, whereas the Bash script itself can exit.

How do you get the EC2 Instance to run this script? Normally, you would use a tool like Packer to create a custom AMI that has the web server installed on it. Since the dummy web server in this example is just a one-liner that uses busybox, you can use a plain Ubuntu 20.04 AMI and run the “Hello, World” script as part of the EC2 Instance’s User Data configuration. When you launch an EC2 Instance, you have the option of passing either a shell script or cloud-init directive to User Data, and the EC2 Instance will execute it during its very first boot. You pass a shell script to User Data by setting the user_data argument in your Terraform code as follows:

resource "aws_instance" "example" {

ami = "ami-0fb653ca2d3203ac1"

instance_type = "t2.micro" user_data = <<-EOF

#!/bin/bash

echo "Hello, World" > index.html

nohup busybox httpd -f -p 8080 &

EOF

user_data_replace_on_change = true

tags = {

Name = "terraform-example"

}

}

Two things to notice about the preceding code:

The

<<-EOFandEOFare Terraform’s heredoc syntax, which allows you to create multiline strings without having to insert\ncharacters all over the place.The

user_data_replace_on_changeparameter is set totrueso that when you change theuser_dataparameter and runapply, Terraform will terminate the original instance and launch a totally new one. Terraform’s default behavior is to update the original instance in place, but since User Data runs only on the very first boot, and your original instance already went through that boot process, you need to force the creation of a new instance to ensure your new User Data script actually gets executed.

You need to do one more thing before this web server works. By default, AWS does not allow any incoming or outgoing traffic from an EC2 Instance. To allow the EC2 Instance to receive traffic on port 8080, you need to create a security group:

resource "aws_security_group" "instance" {

name = "terraform-example-instance" ingress {

from_port = 8080

to_port = 8080

protocol = "tcp"

cidr_blocks = ["0.0.0.0/0"]

}

}

This code creates a new resource called aws_security_group (notice how all resources for the AWS Provider begin with aws_) and specifies that this group allows incoming TCP requests on port 8080 from the CIDR block 0.0.0.0/0. CIDR blocks are a concise way to specify IP address ranges. For example, a CIDR block of 10.0.0.0/24 represents all IP addresses between 10.0.0.0 and 10.0.0.255. The CIDR block 0.0.0.0/0 is an IP address range that includes all possible IP addresses, so this security group allows incoming requests on port 8080 from any IP.

Simply creating a security group isn’t enough; you need to tell the EC2 Instance to actually use it by passing the ID of the security group into the vpc_security_group_ids argument of the aws_instance resource. To do that, you first need to learn about Terraform expressions.

An expression in Terraform is anything that returns a value. You’ve already seen the simplest type of expressions, literals, such as strings (e.g., “ami-0fb653ca2d3203ac1”) and numbers (e.g., 5). Terraform supports many other types of expressions that you’ll see throughout this blog post series.

One particularly useful type of expression is a reference, which allows you to access values from other parts of your code. To access the ID of the security group resource, you are going to need to use a resource attribute reference, which uses the following syntax:

<PROVIDER>_<TYPE>.<NAME>.<ATTRIBUTE>

where PROVIDER is the name of the provider (e.g., aws), TYPE is the type of resource (e.g., security_group), NAME is the name of that resource (e.g., the security group is named “instance”), and ATTRIBUTE is either one of the arguments of that resource (e.g., name) or one of the attributes exported by the resource (you can find the list of available attributes in the documentation for each resource). The security group exports an attribute called id, so the expression to reference it will look like this:

aws_security_group.instance.id

You can use this security group ID in the vpc_security_group_ids argument of the aws_instance as follows:

resource "aws_instance" "example" {

ami = "ami-0fb653ca2d3203ac1"

instance_type = "t2.micro"

vpc_security_group_ids = [aws_security_group.instance.id] user_data = <<-EOF

#!/bin/bash

echo "Hello, World" > index.html

nohup busybox httpd -f -p 8080 &

EOF

user_data_replace_on_change = true

tags = {

Name = "terraform-example"

}

}

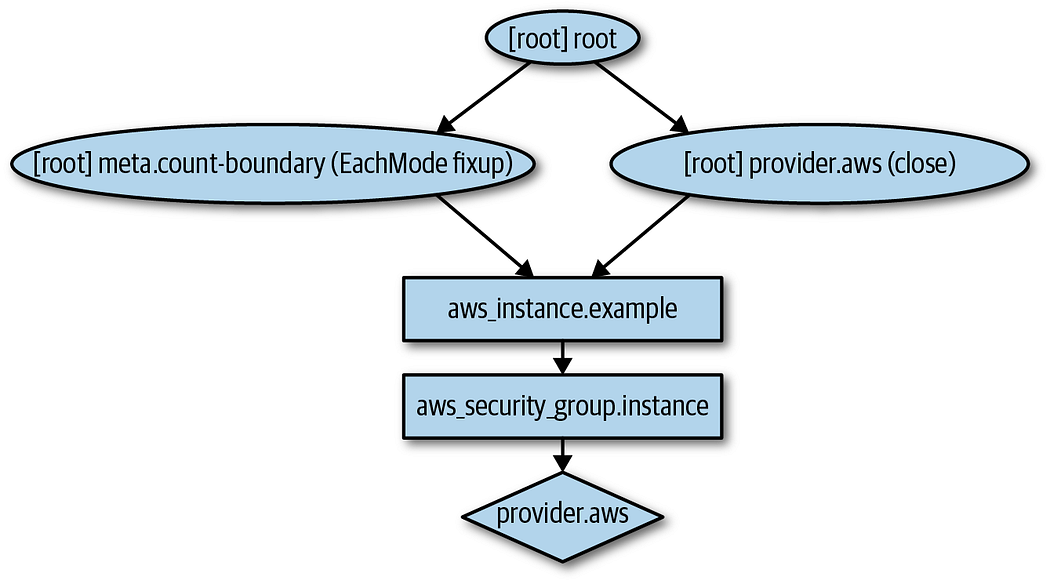

When you add a reference from one resource to another, you create an implicit dependency. Terraform parses these dependencies, builds a dependency graph from them, and uses that to automatically determine in which order it should create resources. For example, if you were deploying this code from scratch, Terraform would know that it needs to create the security group before the EC2 Instance, because the EC2 Instance references the ID of the security group. You can even get Terraform to show you the dependency graph by running the graph command:

$ terraform graph

digraph {

compound = "true"

newrank = "true"

subgraph "root" {

"[root] aws_instance.example"

[label = "aws_instance.example", shape = "box"]

"[root] aws_security_group.instance"

[label = "aws_security_group.instance", shape = "box"]

"[root] provider.aws"

[label = "provider.aws", shape = "diamond"]

"[root] aws_instance.example" ->

"[root] aws_security_group.instance"

"[root] aws_security_group.instance" ->

"[root] provider.aws"

"[root] meta.count-boundary (EachMode fixup)" ->

"[root] aws_instance.example"

"[root] provider.aws (close)" ->

"[root] aws_instance.example"

"[root] root" ->

"[root] meta.count-boundary (EachMode fixup)"

"[root] root" ->

"[root] provider.aws (close)"

}

}

The output is in a graph description language called DOT, which you can turn into an image, similar to the dependency graph shown below, by using a desktop app such as Graphviz or web app like GraphvizOnline.

When Terraform walks your dependency tree, it creates as many resources in parallel as it can, which means that it can apply your changes fairly efficiently. That’s the beauty of a declarative language: you just specify what you want, and Terraform determines the most efficient way to make it happen.

If you run the apply command, you’ll see that Terraform wants to create a security group and replace the EC2 Instance with a new one that has the new user data:

$ terraform apply

(...)

Terraform will perform the following actions:

# aws_instance.example must be replaced

-/+ resource "aws_instance" "example" {

ami = "ami-0fb653ca2d3203ac1"

~ availability_zone = "us-east-2c" -> (known after apply)

~ instance_state = "running" -> (known after apply)

instance_type = "t2.micro"

(...)

+ user_data = "c765373..." # forces replacement

~ vpc_security_group_ids = [

- "sg-871fa9ec",

] -> (known after apply)

(...)

}

# aws_security_group.instance will be created

+ resource "aws_security_group" "instance" {

+ arn = (known after apply)

+ description = "Managed by Terraform"

+ egress = (known after apply)

+ id = (known after apply)

+ ingress = [

+ {

+ cidr_blocks = [

+ "0.0.0.0/0",

]

+ description = ""

+ from_port = 8080

+ ipv6_cidr_blocks = []

+ prefix_list_ids = []

+ protocol = "tcp"

+ security_groups = []

+ self = false

+ to_port = 8080

},

]

+ name = "terraform-example-instance"

+ owner_id = (known after apply)

+ revoke_rules_on_delete = false

+ vpc_id = (known after apply)

}

Plan: 2 to add, 0 to change, 1 to destroy.

Do you want to perform these actions?

Terraform will perform the actions described above.

Only 'yes' will be accepted to approve.

Enter a value:

The -/+ in the plan output means “replace”; look for the text “forces replacement” in the plan output to figure out what is forcing Terraform to do a replacement. Since you set user_data_replace_on_change to true and changed the user_data parameter, this will force a replacement, which means that the original EC2 Instance will be terminated and a completely new Instance will be created. It’s worth mentioning that while the web server is being replaced, any users of that web server would experience downtime; you’ll see how to do a zero-downtime deployment with Terraform later in this blog post series.

Since the plan looks good, enter yes, and you’ll see your new EC2 Instance deploying:

If you click your new Instance, you can find its public IP address in the description panel at the bottom of the screen. Give the Instance a minute or two to boot up, and then use a web browser or a tool like curl to make an HTTP request to this IP address at port 8080:

$ curl http://<EC2_INSTANCE_PUBLIC_IP>:8080

Hello, World

Yay! You now have a working web server running in AWS!

$ curl http://<EC2_INSTANCE_PUBLIC_IP>:8080

Hello, World

You might have noticed that the web server code has the port 8080 duplicated in both the security group and the User Data configuration. This violates the Don’t Repeat Yourself (DRY) principle: every piece of knowledge must have a single, unambiguous, authoritative representation within a system (from The Pragmatic Programmer). If you have the port number in two places, it’s easy to update it in one place but forget to make the same change in the other place.

To allow you to make your code more DRY and more configurable, Terraform allows you to define input variables. Here’s the syntax for declaring a variable:

variable "NAME" {

[CONFIG ...]

}

The body of the variable declaration can contain the following optional parameters:

description: It’s always a good idea to use this parameter to document how a variable is used. Your teammates will be able to see this description not only while reading the code but also when running theplanorapplycommands (you’ll see an example of this shortly).default: There are a number of ways to provide a value for the variable, including passing it in at the command line (using the-varoption), via a file (using the-var-fileoption), or via an environment variable (Terraform looks for environment variables of the nameTF_VAR_<variable_name>). If no value is passed in, the variable will fall back to this default value. If there is no default value, Terraform will interactively prompt the user for one.type: This allows you to enforce type constraints on the variables a user passes in. Terraform supports a number of type constraints, includingstring,number,bool,list,map,set,object,tuple, andany. It’s always a good idea to define a type constraint to catch simple errors. If you don’t specify a type, Terraform assumes the type isany.validation: This allows you to define custom validation rules for the input variable that go beyond basic type checks, such as enforcing minimum or maximum values on a number.sensitive: If you set this parameter totrueon an input variable, Terraform will not log it when you runplanorapply. You should use this on any secrets you pass into your Terraform code via variables: e.g., passwords, API keys, etc. See A comprehensive guide to managing secrets in your Terraform code for more info.

In the web server example, what you need is a variable that stores the port number:

variable "server_port" {

description = "The port the server will use for HTTP requests"

type = number

}

Note that the server_port input variable has no default, so if you run the apply command now, Terraform will interactively prompt you to enter a value for server_port and show you the description of the variable:

$ terraform apply

var.server_port

The port the server will use for HTTP requests

Enter a value:

If you don’t want to deal with an interactive prompt, you can provide a value for the variable via the -var command-line option:

$ terraform plan -var "server_port=8080"

You could also set the variable via an environment variable named TF_VAR_<name>, where <name> is the name of the variable you’re trying to set:

$ export TF_VAR_server_port=8080

$ terraform plan

And if you don’t want to deal with remembering extra command-line arguments every time you run plan or apply, you can specify a default value:

variable "server_port" {

description = "The port the server will use for HTTP requests"

type = number

default = 8080

}

To use the value from an input variable in your Terraform code, you can use a new type of expression called a variable reference, which has the following syntax:

var.<VARIABLE_NAME>

For example, here is how you can set the from_port and to_port parameters of the security group to the value of the server_port variable:

resource "aws_security_group" "instance" {

name = "terraform-example-instance" ingress {

from_port = var.server_port

to_port = var.server_port

protocol = "tcp"

cidr_blocks = ["0.0.0.0/0"]

}

}

It’s also a good idea to use the same variable when setting the port in the User Data script. To use a reference inside of a string literal, you need to use a new type of expression called an interpolation, which has the following syntax:

"${...}"

You can put any valid reference within the curly braces, and Terraform will convert it to a string. For example, here’s how you can use var.server_port inside of the User Data string:

user_data = <<-EOF

#!/bin/bash

echo "Hello, World" > index.html

nohup busybox httpd -f -p ${var.server_port} &

EOF

In addition to input variables, Terraform also allows you to define output variables by using the following syntax:

output "<NAME>" {

value = <VALUE>

[CONFIG ...]

}

The NAME is the name of the output variable, and VALUE can be any Terraform expression that you would like to output. The CONFIG can contain the following optional parameters:

description: It’s always a good idea to use this parameter to document what type of data is contained in the output variable.sensitive: Set this parameter totrueto instruct Terraform not to log this output at the end ofplanorapply. This is useful if the output variable contains secrets such as passwords or private keys. Note that if your output variable references an input variable or resource attribute marked withsensitive = true, you are required to mark the output variable withsensitive = trueas well to indicate you are intentionally outputting a secret.depends_on: Normally, Terraform automatically figures out your dependency graph based on the references within your code, but in rare situations, you have to give it extra hints. For example, perhaps you have an output variable that returns the IP address of a server, but that IP won’t be accessible until a security group (firewall) is properly configured for that server. In that case, you may explicitly tell Terraform there is a dependency between the IP address output variable and the security group resource usingdepends_on.

For example, instead of having to manually poke around the EC2 console to find the IP address of your server, you can provide the IP address as an output variable:

output "public_ip" {

value = aws_instance.example.public_ip

description = "The public IP address of the web server"

}

This code uses an attribute reference again, this time referencing the public_ip attribute of the aws_instance resource. If you run the apply command again, Terraform will not apply any changes (because you haven’t changed any resources), but it will show you the new output at the very end:

$ terraform apply

(...)

aws_security_group.instance: Refreshing state... [id=sg-078ccb4f953]

aws_instance.example: Refreshing state... [id=i-028cad2d4e6bddec6]

Apply complete! Resources: 0 added, 0 changed, 0 destroyed.

Outputs:

public_ip = "54.174.13.5"

As you can see, output variables show up in the console after you run terraform apply, which users of your Terraform code might find useful (e.g., you now know what IP to test after the web server is deployed). You can also use the terraform output command to list all outputs without applying any changes:

$ terraform output

public_ip = "54.174.13.5"

And you can run terraform output <OUTPUT_NAME> to see the value of a specific output called <OUTPUT_NAME>:

$ terraform output public_ip

"54.174.13.5"

This is particularly handy for scripting. For example, you could create a deployment script that runs terraform apply to deploy the web server, uses terraform output public_ip to grab its public IP, and runs curl on the IP as a quick smoke test to validate that the deployment worked.

Input and output variables are also essential ingredients in creating configurable and reusable infrastructure code, a topic you’ll see more of in Part 4 of this series.

This is particularly handy for scripting. For example, you could create a deployment script that runs terraform apply to deploy the web server, uses terraform output public_ip to grab its public IP, and runs curl on the IP as a quick smoke test to validate that the deployment worked.

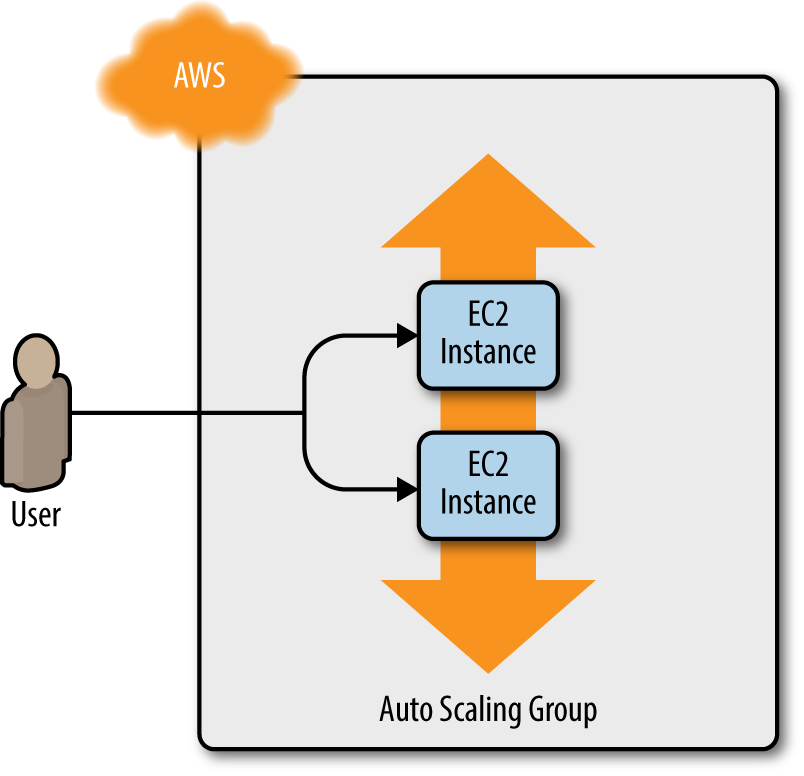

Running a single server is a good start, but in the real world, a single server is a single point of failure. If that server crashes, or if it becomes overloaded from too much traffic, users will be unable to access your site. The solution is to run a cluster of servers, routing around servers that go down and adjusting the size of the cluster up or down based on traffic (for more info, check out A Comprehensive Guide to Building a Scalable Web App on Amazon Web Services).

Managing such a cluster manually is a lot of work. Fortunately, you can let AWS take care of it for you by using an Auto Scaling Group (ASG). An ASG takes care of a lot of tasks for you completely automatically, including launching a cluster of EC2 Instances, monitoring the health of each Instance, replacing failed Instances, and adjusting the size of the cluster in response to load.

The first step in creating an ASG is to create a launch configuration, which specifies how to configure each EC2 Instance in the ASG. The aws_launch_configuration resource uses almost the same parameters as the aws_instance resource, although it doesn’t support tags (you’ll handle these in the aws_autoscaling_group resource later) or the user_data_replace_on_change parameter (ASGs launch new instances by default, so you don’t need this parameter), and two of the parameters have different names (ami is now image_id, and vpc_security_group_ids is now security_groups), so replace aws_instance with aws_launch_configuration as follows:

resource "aws_launch_configuration" "example" {

image_id = "ami-0fb653ca2d3203ac1"

instance_type = "t2.micro"

security_groups = [aws_security_group.instance.id]

user_data = <<-EOF

#!/bin/bash

echo "Hello, World" > index.html

nohup busybox httpd -f -p ${var.server_port} &

EOF

}

Now you can create the ASG itself using the aws_autoscaling_group resource:

resource "aws_autoscaling_group" "example" {

launch_configuration = aws_launch_configuration.example.name min_size = 2

max_size = 10

tag {

key = "Name"

value = "terraform-asg-example"

propagate_at_launch = true

}

}

This ASG will run between 2 and 10 EC2 Instances (defaulting to 2 for the initial launch), each tagged with the name terraform-asg-example. Note that the ASG uses a reference to fill in the launch configuration name. This leads to a problem: launch configurations are immutable, so if you change any parameter of your launch configuration, Terraform will try to replace it. Normally, when replacing a resource, Terraform would delete the old resource first and then creates its replacement, but because your ASG now has a reference to the old resource, Terraform won’t be able to delete it.

To solve this problem, you can use a lifecycle setting. Every Terraform resource supports several lifecycle settings that configure how that resource is created, updated, and/or deleted. A particularly useful lifecycle setting is create_before_destroy. If you set create_before_destroy to true, Terraform will invert the order in which it replaces resources, creating the replacement resource first (including updating any references that were pointing at the old resource to point to the replacement) and then deleting the old resource. Add the lifecycle block to your aws_launch_configuration as follows:

resource "aws_launch_configuration" "example" {

image_id = "ami-0fb653ca2d3203ac1"

instance_type = "t2.micro"

security_groups = [aws_security_group.instance.id]

user_data = <<-EOF

#!/bin/bash

echo "Hello, World" > index.html

nohup busybox httpd -f -p ${var.server_port} &

EOF # Required when using a launch configuration with an ASG.

lifecycle {

create_before_destroy = true

}

}

There’s also one other parameter that you need to add to your ASG to make it work: subnet_ids. This parameter specifies to the ASG into which VPC subnets the EC2 Instances should be deployed. Each subnet lives in an isolated AWS AZ (that is, isolated datacenter), so by deploying your Instances across multiple subnets, you ensure that your service can keep running even if some of the datacenters have an outage. You could hardcode the list of subnets, but that won’t be maintainable or portable, so a better option is to use data sources to get the list of subnets in your AWS account.

A data source represents a piece of read-only information that is fetched from the provider (in this case, AWS) every time you run Terraform. Adding a data source to your Terraform configurations does not create anything new; it’s just a way to query the provider’s APIs for data and to make that data available to the rest of your Terraform code. Each Terraform provider exposes a variety of data sources. For example, the AWS Provider includes data sources to look up VPC data, subnet data, AMI IDs, IP address ranges, the current user’s identity, and much more.

The syntax for using a data source is very similar to the syntax of a resource:

data "<PROVIDER>_<TYPE>" "<NAME>" {

[CONFIG ...]

}

Here, PROVIDER is the name of a provider (e.g., aws), TYPE is the type of data source you want to use (e.g., vpc), NAME is an identifier you can use throughout the Terraform code to refer to this data source, and CONFIG consists of one or more arguments that are specific to that data source. For example, here is how you can use the aws_vpc data source to look up the data for your Default VPC:

data "aws_vpc" "default" {

default = true

}

Note that with data sources, the arguments you pass in are typically search filters that indicate to the data source what information you’re looking for. With the aws_vpc data source, the only filter you need is default = true, which directs Terraform to look up the Default VPC in your AWS account.

To get the data out of a data source, you use the following attribute reference syntax:

data.<PROVIDER>_<TYPE>.<NAME>.<ATTRIBUTE>

For example, to get the ID of the VPC from the aws_vpc data source, you would use the following:

data.aws_vpc.default.id

You can combine this with another data source, aws_subnets, to look up the subnets within that VPC:

data "aws_subnets" "default" {

filter {

name = "vpc-id"

values = [data.aws_vpc.default.id]

}

}

Finally, you can pull the subnet IDs out of the aws_subnets data source and tell your ASG to use those subnets via the (somewhat oddly named) vpc_zone_identifier argument:

resource "aws_autoscaling_group" "example" {

launch_configuration = aws_launch_configuration.example.name

vpc_zone_identifier = data.aws_subnets.default.ids min_size = 2

max_size = 10

tag {

key = "Name"

value = "terraform-asg-example"

propagate_at_launch = true

}

} min_size = 2

max_size = 10

At this point, you can deploy your ASG, but you’ll have a small problem: you now have multiple servers, each with its own IP address, but you typically want to give your end users only a single IP to use. One way to solve this problem is to deploy a load balancer to distribute traffic across your servers and to give all your users the IP (actually, the DNS name) of the load balancer. Creating a load balancer that is highly available and scalable is a lot of work. Once again, you can let AWS take care of it for you, this time by using Amazon’s Elastic Load Balancer (ELB) service:

AWS offers three types of load balancers:

Application Load Balancer (ALB). Best suited for load balancing of HTTP and HTTPS traffic. Operates at the application layer (Layer 7) of the Open Systems Interconnection (OSI) model.

Network Load Balancer (NLB). Best suited for load balancing of TCP, UDP, and TLS traffic. Can scale up and down in response to load faster than the ALB (the NLB is designed to scale to tens of millions of requests per second). Operates at the transport layer (Layer 4) of the OSI model.

Classic Load Balancer (CLB). This is the “legacy” load balancer that predates both the ALB and NLB. It can handle HTTP, HTTPS, TCP, and TLS traffic but with far fewer features than either the ALB or NLB. Operates at both the application layer (L7) and transport layer (L4) of the OSI model.

Most applications these days should use either the ALB or the NLB. Because the simple web server example you’re working on is an HTTP app without any extreme performance requirements, the ALB is going to be the best fit.

The ALB consists of several parts:

Listener. Listens on a specific port (e.g., 80) and protocol (e.g., HTTP).

Listener rule. Takes requests that come into a listener and sends those that match specific paths (e.g.,

/fooand/bar) or hostnames (e.g.,foo.example.comandbar.example.com) to specific target groups.Target groups. One or more servers that receive requests from the load balancer. The target group also performs health checks on these servers and sends requests only to healthy nodes.

The first step is to create the ALB itself using the aws_lb resource:

resource "aws_lb" "example" {

name = "terraform-asg-example"

load_balancer_type = "application"

subnets = data.aws_subnets.default.ids

}

Note that the subnets parameter configures the load balancer to use all the subnets in your Default VPC by using the aws_subnets data source. AWS load balancers don’t consist of a single server, but of multiple servers that can run in separate subnets (and, therefore, separate datacenters). AWS automatically scales the number of load balancer servers up and down based on traffic and handles failover if one of those servers goes down, so you get scalability and high availability out of the box.

The next step is to define a listener for this ALB using the aws_lb_listener resource:

resource "aws_lb_listener" "http" {

load_balancer_arn = aws_lb.example.arn

port = 80

protocol = "HTTP"

# By default, return a simple 404 page

default_action {

type = "fixed-response"

fixed_response {

content_type = "text/plain"

message_body = "404: page not found"

status_code = 404

}

}

}

This listener configures the ALB to listen on the default HTTP port, port 80, use HTTP as the protocol, and send a simple 404 page as the default response for requests that don’t match any listener rules.

Note that, by default, all AWS resources, including ALBs, don’t allow any incoming or outgoing traffic, so you need to create a new security group specifically for the ALB. This security group should allow incoming requests on port 80 so that you can access the load balancer over HTTP, and allow outgoing requests on all ports so that the load balancer can perform health checks:

resource "aws_security_group" "alb" {

name = "terraform-example-alb" # Allow inbound HTTP requests

ingress {

from_port = 80

to_port = 80

protocol = "tcp"

cidr_blocks = ["0.0.0.0/0"]

}

# Allow all outbound requests

egress {

from_port = 0

to_port = 0

protocol = "-1"

cidr_blocks = ["0.0.0.0/0"]

}

}

You’ll need to tell the aws_lb resource to use this security group via the security_groups argument:

resource "aws_lb" "example" {

name = "terraform-asg-example"

load_balancer_type = "application"

subnets = data.aws_subnets.default.ids

security_groups = [aws_security_group.alb.id]

}

Next, you need to create a target group for your ASG using the aws_lb_target_group resource:

resource "aws_lb_target_group" "asg" {

name = "terraform-asg-example"

port = var.server_port

protocol = "HTTP"

vpc_id = data.aws_vpc.default.id

health_check {

path = "/"

protocol = "HTTP"

matcher = "200"

interval = 15

timeout = 3

healthy_threshold = 2

unhealthy_threshold = 2

}

}

This target group will health check your Instances by periodically sending an HTTP request to each Instance and will consider the Instance “healthy” only if the Instance returns a response that matches the configured matcher (e.g., you can configure a matcher to look for a 200 OK response). If an Instance fails to respond, perhaps because that Instance has gone down or is overloaded, it will be marked as “unhealthy,” and the target group will automatically stop sending traffic to it to minimize disruption for your users.

How does the target group know which EC2 Instances to send requests to? You could attach a static list of EC2 Instances to the target group using the aws_lb_target_group_attachment resource, but with an ASG, Instances can launch or terminate at any time, so a static list won’t work. Instead, you can take advantage of the first-class integration between the ASG and the ALB. Go back to the aws_autoscaling_group resource, and set its target_group_arns argument to point at your new target group:

resource "aws_autoscaling_group" "example" {

launch_configuration = aws_launch_configuration.example.name

vpc_zone_identifier = data.aws_subnets.default.ids target_group_arns = [aws_lb_target_group.asg.arn]

health_check_type = "ELB" min_size = 2

max_size = 10

tag {

key = "Name"

value = "terraform-asg-example"

propagate_at_launch = true

}

}

You should also update the health_check_type to “ELB”. The default health_check_type is “EC2”, which is a minimal health check that considers an Instance unhealthy only if the AWS hypervisor says the VM is completely down or unreachable. The “ELB” health check is more robust, because it instructs the ASG to use the target group’s health check to determine whether an Instance is healthy and to automatically replace Instances if the target group reports them as unhealthy. That way, Instances will be replaced not only if they are completely down but also if, for example, they’ve stopped serving requests because they ran out of memory or a critical process crashed.

Finally, it’s time to tie all these pieces together by creating listener rules using the aws_lb_listener_rule resource:

resource "aws_lb_listener_rule" "asg" {

listener_arn = aws_lb_listener.http.arn

priority = 100

condition {

path_pattern {

values = ["*"]

}

}

action {

type = "forward"

target_group_arn = aws_lb_target_group.asg.arn

}

}

The preceding code adds a listener rule that sends requests that match any path to the target group that contains your ASG.

There’s one last thing to do before you deploy the load balancer — replace the old public_ip output of the single EC2 Instance you had before with an output that shows the DNS name of the ALB:

output "alb_dns_name" {

value = aws_lb.example.dns_name

description = "The domain name of the load balancer"

}

Run terraform apply, and read through the plan output. You should see that your original single EC2 Instance is being removed, and in its place, Terraform will create a launch configuration, ASG, ALB, and a security group. If the plan looks good, type yes and hit Enter. When apply completes, you should see the alb_dns_name output:

Outputs:

alb_dns_name = "terraform-asg-example-1.us-east-2.elb.amazonaws.com"

Copy down this URL. It’ll take a couple minutes for the Instances to boot and show up as healthy in the ALB. In the meantime, you can inspect what you’ve deployed. Open up the ASG section of the EC2 console, and you should see that the ASG has been created:

If you switch over to the Instances tab, you’ll see the two EC2 Instances launching:

If you click the Load Balancers tab, you’ll see your ALB:

Finally, if you click the Target Groups tab, you can find your target group:

If you click your target group and find the Targets tab in the bottom half of the screen, you can see your Instances registering with the target group and going through health checks. Wait for the Status indicator to indicate “healthy” for both of them. This typically takes one to two minutes. When you see it, test the alb_dns_name output you copied earlier:

$ curl http://<alb_dns_name>

Hello, World

Success! The ALB is routing traffic to your EC2 Instances. Each time you access the URL, it’ll pick a different Instance to handle the request. You now have a fully working cluster of web servers!

At this point, you can see how your cluster responds to firing up new Instances or shutting down old ones. For example, go to the Instances tab and terminate one of the Instances by selecting its checkbox, clicking the Actions button at the top, and then setting the Instance State to Terminate. Continue to test the ALB URL, and you should get a 200 OK for each request, even while terminating an Instance, because the ALB will automatically detect that the Instance is down and stop routing to it. Even more interesting, a short time after the Instance shuts down, the ASG will detect that fewer than two Instances are running and automatically launch a new one to replace it (self-healing!). You can also see how the ASG resizes itself by adding a desired_capacity parameter to your Terraform code and rerunning apply.

At this point, you can see how your cluster responds to firing up new Instances or shutting down old ones. For example, go to the Instances tab, and terminate one of the Instances by selecting its checkbox, selecting the “Actions” button at the top, and setting the “Instance State” to “Terminate.” Continue to test the CLB URL and you should get a “200 OK” for each request, even while terminating an Instance, as the CLB will automatically detect that the Instance is down and stop routing to it. Even more interestingly, a short time after the Instance shuts down, the ASG will detect that fewer than 2 Instances are running, and automatically launch a new one to replace it (self healing!). You can also see how the ASG resizes itself by changing the min_size and max_size parameters or adding a desired_size parameter to your Terraform code, and re-running apply.

When you’re done experimenting with Terraform, either at the end of this blog post, or at the end of future posts, it’s a good idea to remove all of the resources you created so that AWS doesn’t charge you for them. Because Terraform keeps track of what resources you created, cleanup is simple. All you need to do is run the destroy command:

$ terraform destroy

(...)

Terraform will perform the following actions:

# aws_autoscaling_group.example will be destroyed

- resource "aws_autoscaling_group" "example" {

(...)

}

# aws_launch_configuration.example will be destroyed

- resource "aws_launch_configuration" "example" {

(...)

}

# aws_lb.example will be destroyed

- resource "aws_lb" "example" {

(...)

}

(...)

Plan: 0 to add, 0 to change, 8 to destroy.

Do you really want to destroy all resources?

Terraform will destroy all your managed infrastructure, as shown

above.

There is no undo. Only 'yes' will be accepted to confirm.

Enter a value:

It goes without saying that you should rarely, if ever, run destroy in a production environment! There’s no “undo” for the destroy command, so Terraform gives you one final chance to review what you’re doing, showing you the list of all the resources you’re about to delete, and prompting you to confirm the deletion. If everything looks good, type yes and hit Enter; Terraform will build the dependency graph and delete all of the resources in the correct order, using as much parallelism as possible. In a minute or two, your AWS account should be clean again.

Note that later in this blog post series, you will continue to develop this example, so don’t delete the Terraform code! However, feel free to run destroy on the actual deployed resources whenever you want. After all, the beauty of infrastructure as code is that all of the information about those resources is captured in code, so you can re-create all of them at any time with a single command: terraform apply. In fact, you might want to commit your latest changes to Git so that you can keep track of the history of your infrastructure.

Enter a value:

You now have a basic grasp of how to use Terraform. The declarative language makes it easy to describe exactly the infrastructure you want to create. The plan command allows you to verify your changes and catch bugs before deploying them. Variables, references, and dependencies allow you to remove duplication from your code and make it highly configurable.

However, you’ve only scratched the surface. In Part 3 of the series, How to manage Terraform state, you’ll learn how Terraform keeps track of what infrastructure it has already created, and the profound impact that has on how you should structure your Terraform code. In Part 4 of this series, you’ll see how to create reusable infrastructure with Terraform modules.

You now have a basic grasp of how to use Terraform. The declarative language makes it easy to describe exactly the infrastructure you want to create. The plan command allows you to verify your changes and catch bugs before deploying them. Variables, references, and dependencies allow you to keep code DRY and efficient.

However, we’ve only just scratched the surface. In Part 3 of the series, How to manage Terraform state, we’ll show how Terraform keeps track of what infrastructure it has already created, and the profound impact that has on how you should structure your Terraform code. In Part 4 of the series, we’ll show how to create reusable infrastructure with Terraform modules.

I am Sunil kumar, Please do follow me here and support #devOps #trainwithshubham #github #devopscommunity #devops #cloud #devoparticles #trainwithshubham

Connect with me over linkedin : linkedin.com/in/sunilkumar2807